This article was in the Twin Lakes Visitor in June of 1979.

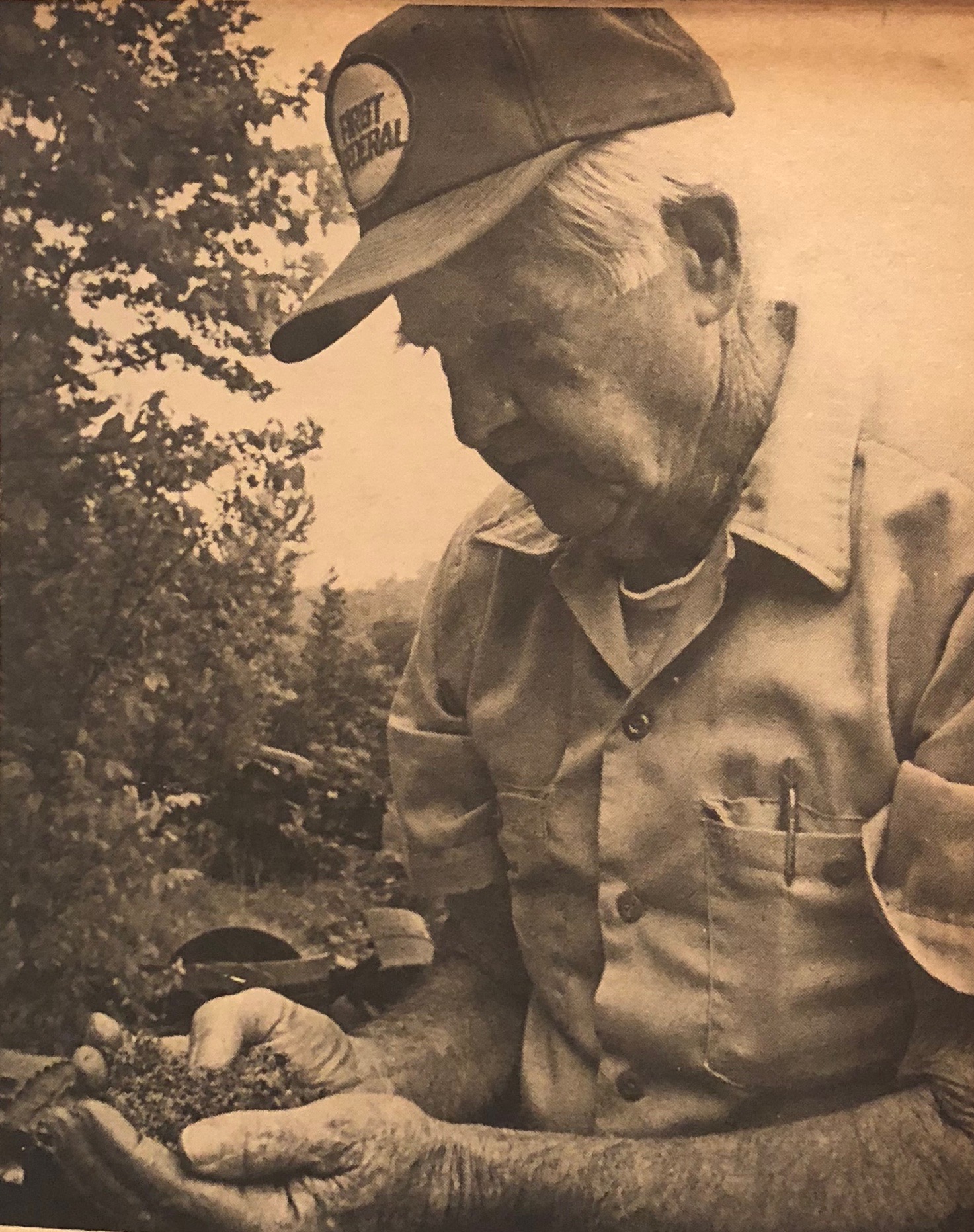

Fred Dirst: the King of Rush Survives

Fred Dirst is really a Hoosier, born in northern Indiana. When he’s asked if he’d tell a little about himself and the Rush area of Arkansas, he replies, ”You want to hear some more lies?”

Yet everyone listens, everyone from tourists passing through, to the National Geographic, which wrote of the Buffalo River, and Fred.

The Buffalo River and Rush is Fred. No one has been there longer or knows more about the area. Ask about the ore, the mines, who lived in which cabin, who ran the store, or even who had the first car in Rush!

“I did. Most of the people had to ride up to Yellville with John Bundy who brought the mail with a mule team and wagon. He charged a quarter.”

Later Dal Tyler drove the mail wagon, but he drank a bit. His real name was Owens, but he lived a while in Dallas, then Tyler, Tex., and came back as Dal Tyler.

“He had a hard time collecting his pension from the Spanish American War because they didn’t have any Dal Tyler on the records, and Dal couldn’t convince them his name was Owens. He charged a dollar for the trip to Yellville.

Fred came to Arkansas with his family in 1906 via Bergman and Dodd City. His father ran the hotel in Rush. It was a two-story building with about 12 rooms upstairs, a long dining room and kitchen downstairs. Room and board was $3 a week, the going rate in most Arkansas mining towns during the first decade of the 20th Century.

The 20th Century was late arriving in Arkansas.

“We didn’t have any electricity, though they talked about putting a dam on the Buffalo to generate some for Rush, but the war ended in 1917 before anyone got around to it.

By 1918 everyone left. The drug store had a soda fountain with no ice. The druggist just walked away one day so everyone else just helped themselves to sodas. The kids had atime in there.”

Rush was the center of zinc mining in northwestern Arkansas. Zinc had been discovered in 1884 at the Morning Star mine, though mining didn’t get underway until 1889. The mine eventually produced a huge chunk of ore weighing 12,750 pounds from a “glory hole,” or pocket of zinc. That chunk is now on display in the Field Museum in Chicago.

It was floated down the Buffalo to Batesville, after being hauled from the mine on a logging wagon pulled by 16 oxen. Then it was transported to Chicago by railroad car and displayed at the World’s Fair Columbian Exposition where it won first premium. Ore now on display in the Smithsonian from the Morning Star mine also won first award at the St Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

“Bill Taylor ran the general store and post office from about 1914 into the 20s. I remember as many as 300 people hanging around the store when the mail came.

Then Sammy Jones had it, and Bill Melton after Sammy. It kept going for a while. Lee Medley ran it up to the early 60s. Since then nothing has been in Rush.”

The creek still runs past the empty decaying general store and cabins along “main street.” There are three cabins, the old mule barn, part of the stone smelter chimney, and another barn further up the hill still standing, but just barely.

Rush Creek dries up in the summer, leaving its stone bed as empty as the town, except for a strong cold spring downstream from the town that continues to carry the crystal clear water down to the Buffalo. It has a slightly metallic, but sweet taste.

It bubbles up from under the road to the mill where the ore was broken up, and settled out from the rock.

Fred walked through the remains of the mill with its gigantic wheels, machinery, and the nearly gone settling pool where the heavy ore was separated from the lighter rock, which was funneled off through pipes down the side of the hill.

“I wish they hadn’t done this,” he said, looking around at the skeleton of the mill the government is tearing down. The government should stay out of Arkansas.”

Since the Buffalo was designated a National Scenic River all of the land along the river had been bought up and now most of the historic landmarks were being torn down, including the mill. It had been a fascinating building with many roof levels and angles almost oriental in its design, yet sprawling and strong.

“I bought over 300 acres on the Buffalo in 1953.” In 1956 the mill was moved down here from Missouri and was operating off and on until 1964, operating on Fred’s land.

“They paid me for a while. We had a lease deal for the land where they set up the mill. But then they stopped paying. After they closed down I put up “no trespassing” signs, but let tourists go through the mill, for a fee. Sometimes people would come in here without asking and I’d ask them if they could read the signs. Once in a while they’d get smart so I carried a pistol.”

Before the summer is over the Rush Creek Mining Company mill will probably be nothing but a scar along the side of the road until the thick brush and trees cover it over and hide it forever.

It’s hard to imagine the Old Town of Rush, settled in the late 19th Century by would-be silver miners (they never found any silver), and the new town of Rush, created by the zinc boom during the first World War, with several hotels, restaurants, three pool halls, and seven barbers. Fred first worked in the Lonny Boy mine, across the river from Rush, and has worked may of the mines in the area, including the Morning Star, the Red Cloud, Edith Mill, Yellow Rose.

Most of the mines are caved in now, but the Philadelphia and Monte Cristo, though on private property, are accessible.

Restless in his youth, Fred spent three summers in Wyoming from 1917-19 herding sheep and cattle.

“I had 2,000 sheep out there and got pretty handy with a horse. Also spent some time on the White River working on the barges. They were pushed with a paddle wheel boat. But most of the time I was mining. Went up to Oklahoma to the Picher District in the northeast corner, Tri State mining area, after the army.”

The army stint was spent in Hawaii where Fred went to school for six months “to keep from doing duty,” and where he excelled at Rescue Racing.

“We’d race on horseback a 100-yard dash, pick up a man and race back.”

“My partner was a little Mexican lightweight and easy to pick up. Our commanding officer gave me his polo pony to ride so nobody could beat us. We were supposed to have a rescue race meet one day, but a load of hay had arrived that I was going to have to help unload, so instead of staying around for the meet and the work, I got a pass and left for the day. The CO wasn’t happy.”

School, other than the six months in the army, ended for Fred after the fourth grade and a couple of months of the sixth grade. He ran away in between fourth and sixth, and then again after a few months of the sixth grade. “Had enough of that.”

Swimming on Waikiki Beach during leave one day, Fred swam into Gertrude Etterly who, three years later, was to become the first woman to swim the English Channel. Fred says she was a stronger swimmer than he was.

Obviously, he hasn’t really lacked an education, having learned along the way and read extensively. His memory and retention are to be envied. He’s also proud of the local residents who have become successful.

“Bill and Harold Urschel lived in that cabin, the one we call the ‘Rush Hilton’. Harold’s now a heart surgeon at Baylor in Dallas, and Bill’s a urologist, I think in California.”

The Rush Hilton has a bathhouse which included not just an outhouse, but a tub. Water was pumped up the hill from the creek into a tank. It was a good-sized cabin used by various people visiting the area.

Jean and Bill Ballard stayed in it while property hunting. They bought one of the old hotels up the road from Rush but had to leave when the government bought the property. Jean is an accomplished artist who has done excellent sketches of the Rush area. The Ballards have moved to Hot Springs, and the government burned the Rush Hilton.

They’ve also burned down the cabin Fed lived in, which doesn’t make him very happy. He had been living in a trailer down the river until the National Park Service took over. Even though he’s talked of leaving the Rush area, he only got about 10 miles from home and now lives on the Buffalo Point road across from his canoe rental service.

His collection of photos and letters from people all over the country is extensive, and includes an autographed copy of Roger Tory Peterson’s ‘Field Guide to the Birds’ and letters from Screen Gems and Coca-Cola (for when he served as guide on the river while they were shooting commercials), archeologists and the National Geographic.

Fred claims he’s allergic to work, and certainly has made efforts to get out of doing any. He did pull four mines on his property since 1953 which he sold to either paint or chemical companies in Kansas and Illinois. He didn’t say who actually did the work.

After major surgery a couple of years ago, Fred has confined activities to his fee collecting for the Rush landing, tours of the mill and scant attention to the canoe rental business ran by his son.

Now, with the National Park Service taking over the river, and tearing down the ill, there isn’t much left - except Fred, who has so much more to tell than can be put together at any one time. An astute admirer sent Fred a short poem a few years back - as follows: